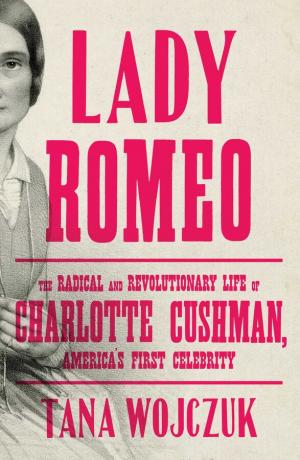

Tana Wojczuk’s Lady Romeo: The Radical and Revolutionary Life of Charlotte Cushman, America’s First Celebrity not only recounts the fascinating story of one of the nineteenth century’s most famous actresses in the English-speaking world, but it also very smartly interweaves revealing historical threads of the United States. Wojczuk never loses track of Cushman’s narrative, reminding the reader only when it’s profitable to do so of the specific context she lived and worked within. The central narrative is briskly propelled but not breezy, rich with deeply researched details that never serve as mere set dressing, offering instead vivid, telling images and subtle but significant historical observations. We learn about Cushman’s childhood as a self-described “tomboy,” her acting process, her business acumen, and her copious letter writing alongside descriptions of the American theater of the day, not to mention reminders of the relevant events like the War of 1812, the financial crisis of 1837, the Compromise of 1850, and the lead-up to the Civil War.

By the end of the book, the reader has an intimate sense of who Charlotte Cushman was as a person and a clear sense of what she meant as a personage. Because Wojczuk’s novelist’s eye is balanced by her historical compass, Lady Romeo promises to reach a wider audience than two critical predecessors, Joseph Leach’s Bright Particular Star: The Life & Times of Charlotte Cushman (1970), which suffers from explaining away Cushman’s romantic relationships with women as “nothing that might not have appeared in any number of Victorian expressions of female friendships,” and Lisa Merrill’s When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators (1999), which is thorough and convincing but strikes a perhaps too-academic tone to be enjoyed by a general audience.

By the end of the book, the reader has an intimate sense of who Charlotte Cushman was as a person and a clear sense of what she meant as a personage. Because Wojczuk’s novelist’s eye is balanced by her historical compass, Lady Romeo promises to reach a wider audience than two critical predecessors, Joseph Leach’s Bright Particular Star: The Life & Times of Charlotte Cushman (1970), which suffers from explaining away Cushman’s romantic relationships with women as “nothing that might not have appeared in any number of Victorian expressions of female friendships,” and Lisa Merrill’s When Romeo Was a Woman: Charlotte Cushman and Her Circle of Female Spectators (1999), which is thorough and convincing but strikes a perhaps too-academic tone to be enjoyed by a general audience.

As an editor of the North American Review, I also can’t help (selfishly) but connect the trajectory of Charlotte Cushman’s career to the magazine itself, founded as it was in 1815 in Boston, the same city as Cushman’s birth in 1816. In some important ways, her life parallels the NAR’s, each of them anxious to demonstrate to the wider world a uniquely American artistic identity worthy of respected European models. The early editors of the NAR were young men of Harvard who had traveled and studied in Europe, returning to the United States with a newly expanded cultural vision, not quite the formal neoclassical aesthetics of their fathers and not quite the open expressiveness of the Romantics, but a hybrid of the two. They founded the NAR in part to discover and celebrate new American art that was already worthy of attention but also to help shape and inform the future of American art with this hybrid vision in mind. Cushman, too, found her way by traveling abroad, after relative failures onstage in the United States, becoming the famous actress she is remembered as abroad. I like to imagine the former NAR editor Edward Everett in February 1845, then ambassador to the United Kingdom, seeing Cushman as Lady Macbeth at the Princess Theatre in London and being pleased at the achievement of his fellow American, an undeniable artistic declaration of independence.

Fittingly, Everett and Cushman are both buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, along with many other notable New Englanders, among them numerous NAR editors and contributors. As Wojczuk makes clear, however, perhaps the most lasting public memorial to Cushman is not her grave but rather The Angel of the Waters, the statue in the Bethesda Fountain in Central Park designed by sculptor Emma Stebbins, Cushman’s longtime lover. The statue, patterned after Cushman, shares her “strong thighs and broad shoulders.” Some have complained that the Angel is too masculine. In life, as Wojczuk recounts, Cushman's masculine appearance was always noted by critics, sometimes disparagingly but on occasion approvingly, as when a pre-Leaves of Grass Walt Whitman reported in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of Cushman “appearing equipped cast-a-pie in masculine attire—hat, coat, unmentionables and all,” which she was “determined to wear...for the remainder of her days at least, or her maidenhood.” Whitman’s knowing nod to Cushman’s sexuality is only hinted at even years after death, as in Gamaliel Bradford’s celebratory portrait in the North American Review in 1925: “How much direct experience she herself had of love-making is not directly shown to us; but there are interesting stories about it.” These stories, however, are perhaps too interesting for Bradford to believe or investigate further. Luckily, the fullness of Charlotte Cushman as a queer woman in the nineteenth century comes fully to life in the pages of Tana Wojczuk’s Lady Romeo.

Read J. D. Schraffenberger’s recent interview with Tana Wojczuk

Read Tana Wojczuk’s contribution to Every Atom: Reflections on Walt Whitman at 200